Fat Cantor Set

In this post, I talk about the fat Cantor set.

The Cantor Set

One of my favorite constructions in math is the Cantor set, and so by extension I find the generalization pretty fascinating too. The idea is that I can construct an uncountable, compact, nowhere dense and totally disconnected set which has measure whatever I choose. Let’s first start by reviewing the general Cantor construction.

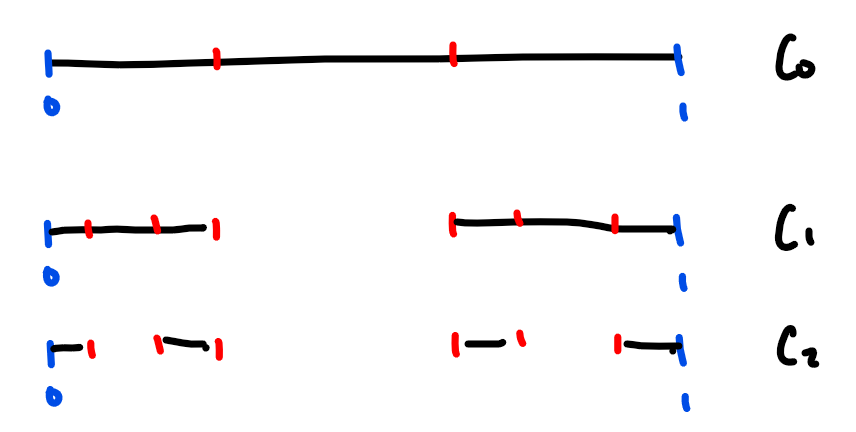

There are two ways I know of how to make the Cantor set, and both are important for the following arguments. The first is a recursive construction. The idea is that we want to remove the “middle thirds” from a sequence of intervals over and over. To formalize that, we start with the set \(C_0 := [0,1],\) and we define \(C_1 := [0,1/3] \cup [2/3, 1].\) You can see we’ve taken the interval \([0,1]\) and removed the interval \([1/3,2/3]\) from it to get \(C_1.\) To get to the next step, we remove the middle third from \([0,1/3]\) and \([2/3,1]\), and then we keep repeating this process ad nauseam. To put this in symbols, we start with

\[C_0 := [0,1],\]and assuming up until \(n-1\) we have \(C_{n-1}\) is a bunch of intervals, as so,

\[C_{n-1} := \bigcup_{j=1}^{m_{n-1}} I_j^{n-1},\]then we can write

\[C_n := \bigcup_{j=1}^{m_{n-1}} [(1/3) I_j^{n-1} \cup (2/3 + (1/3)I_j^{n-1}].\]After relabeling, we can then write

\[C_n := \bigcup_{j=1}^{m_n} I_j^{n}\]and we then repeat the process.

One observation to make is that we can calculate exactly what \(m_{n-1}\) should be in the \(C_{n-1}\) definition. By removing the middle from each interval, we’re essentially adding two intervals, so by induction we get \(m_n = 2^n.\)

Another easy observation to make is that the intervals \(\{I_j^n\}_{j=1}^{2^n}\) are all disjoint for every \(n\). This follows by noting we’re taking disjoint intervals and removing things from them, and this has no chance of accidentally making intervals overlap. An illustration of this process is seen below:

.

.

We now have a sequence of sets \(\{C_n\}_{n=0}^\infty.\) The Cantor set is going to be defined as

\[C := \bigcap_{n =1}^\infty C_n.\]There is an alternative description for the Cantor set which is also very helpful. Consider the space

\[\Omega_2 := \{(a_j)_{j=1}^\infty : a_j \in \{0,1\}\}.\]One way to think about this is the space of sequences of \(0\)s and \(1\)s; i.e. binary sequences.

We define a map \(f : \Omega_2 \rightarrow [0,1]\) by

\[f((a_j)) := \sum_{j=1}^\infty 2a_j 3^{-j}.\]We make two observations about \(f\).

Claim: We have that \(f\) is injective.

Proof: First, observe that \(f((a_j)) \in [0,1]\) for every \((a_j) \in \Omega_2\). This follows, since

\[f((a_j)) = \sum_{j=1}^\infty 2a_j 3^{-j} \leq \sum_{j=1}^\infty 2 \cdot 3^{-j} = 2 \sum_{j=1}^\infty 3^{-j} = 2 \cdot \frac{1}{2} = 1,\]here using the fact that \(a_j \leq 1\) for every \(j\), and

\[f((a_j)) = \sum_{j=1}^\infty 2a_j 3^{-j} \geq \sum_{j=1}^\infty 0 = 0,\]here using the fact that \(a_j \geq 0\) for every \(j\). Next, let’s assume that \(f((a_j)) = f((b_j)).\) Then

\[\sum_{j=1}^\infty 2a_j 3^{-j} = \sum_{j=1}^\infty 2b_j 3^{-j}.\]I can subtract the right hand side from the left hand side to get

\[\sum_{j=1}^\infty 2 (a_j - b_j) 3^{-j} = 0,\]and I can subtract the left hand side from the right to get

\[\sum_{j=1}^\infty 2 (b_j - a_j) 3^{-j} = 0,\]Now suppose \((a_j) \neq (b_j).\) This implies there is some smallest \(n\) so that \(a_j = b_j\) for all \(1 \leq j \leq n-1\) and \(a_n \neq b_n.\) Notice that either \(a_n = 1, b_n = 0\) or \(a_n = 0, b_n = 1\). Let’s assume \(a_n = 1, b_n = 0\) for the moment (the other one will lead to the same argument). Then we may write

\[\sum_{j=1}^\infty 2 (a_j - b_j) 3^{-j} = \sum_{j=1}^{n-1} 2 (a_j - b_j) 3^{-j} + 2 \cdot 3^{-n} + \sum_{j=n+1}^\infty 2(a_j - b_j) 3^{-j} \\ = 2 \cdot 3^{-n} + \sum_{j=n+1}^\infty 2(a_j - b_j) 3^{-j} = 0.\]Now observe that the smallest I can make the sum is by having \(a_j = 0\) for all \(j \geq n+1\) and \(b_j = 1\) for all \(j \geq n+1\). Let’s check what happens:

\[\sum_{j=n+1}^\infty 2(a_j - b_j) 3^{-j} \geq - \sum_{j=n+1}^\infty 2 3^{-j} = - 3^{-n}.\]So using this fact, we have

\[0 = \sum_{j=1}^\infty 2 (a_j - b_j) 3^{-j} = 2 \cdot 3^{-n} - 3^{-n} = 3^{-n} > 0.\]This is a contradiction! Repeating the argument for \(b_n = 1, a_n = 0\), we get that it is impossible for them to disagree at a point. Thus we’ve shown that if \(f((a_j)) = f((b_j)),\) then \((a_j) = (b_j)\). This is exactly injectivity.

The next claim is the more interesting part.

Claim: We have that \(\text{Im}(f) = C,\) the Cantor set. In other words, \(f\) is a bijection onto the Cantor set.

Proof: Take \(x \in C.\) This says that \(x \in C_n\) for every single \(n\). Let’s check what this means in terms of the ternary expansion of a number: If \(x \in C_1\), then this says that either \(0 \leq x \leq 1/3\) or \(2/3 \leq x \leq 1.\) Now the ternary expansion for this \(x\) is a series

\[x = \sum_{j=1}^\infty a_j 3^{-j}.\]The goal is to show that the above conditions tell us either \(a_1 = 0\) or \(a_1 = 2.\) Let’s check: if \(a_1 = 1,\) then the largest that \(x\) could be is if \(a_j = 2\) for \(j \geq 2\), thus

\[x \leq 1/3 + \sum_{j=2}^\infty 2 3^{-j} = 2/3.\]Meanwhile, if \(a_j = 0\) for \(j \geq 2\), we getting

\[x \geq 1/3 + 0 = 1/3.\]Thus if \(a_1 = 1\), this means that \(1/3 \leq x \leq 2/3.\) But this is exactly the set we’ve removed! So \(x \in C_1\) implies \(a_1 \in \{0,2\}.\)

Now assume that \(x \in C_{n-1}\) implies \(a_1, \ldots, a_{n-1} \in \{0,2\}.\) Taking \(x \in C_n\), we see that \(x \in C_{n-1}\), so it remains to just check that \(a_n \neq 1.\) Let \(y \in I_j^{n-1}\) have ternary expansion

\[y = \sum_{j=1}^\infty b_j 3^{-j}.\]Notice that this is transformed to either

\[(1/3)y = \sum_{j=1}^\infty b_j 3^{-j-1}\]or

\[(2/3) + (1/3)y = (2/3) + \sum_{j=1}^\infty b_j 3^{-j-1}.\]For there to be a \(1\) in the \(nth\) location, we would need \(b_{n-1} = 1,\) but this is impossible by the induction hypothesis. Since \(x\) takes one of the two above forms for some \(y \in I_j^{n-1}\), we see this implies that \(a_n \neq 1.\)

Thus every \(x \in C\) has ternary expansion

\[x = \sum_{j=1}^\infty a_j 3^{-j},\]where \(a_j \in \{0,2\}\). We can take \((a_j/2)\) a binary sequence, and we see that \(f((a_j/2)) = x.\) This gives us surjectivity.

So another way to think of the Cantor set is as the image of \(\Omega_2\) under the map above. Observe that \(\Omega_2\) is uncountable by Cantor’s argument, so we get that \(C\) must also be uncountable. To see that \(C\) is compact, observe that it is an intersection of closed sets, which is closed. To see that it is nowhere dense, we need to show that the interior of \(C\) is empty. Fix \(\epsilon > 0\), and examine

\[B_\epsilon(x) = \{y \in [0,1] : |x-y| < \epsilon\}.\]Our goal is to show that for every \(\epsilon > 0\) and every \(x \in C\) we have that \(B_\epsilon(x) \not\subseteq C.\) Fix \(x\) with ternary expansion given by

\[x = \sum_{j=1}^\infty a_j 3^{-j},\]and define \(y\) by

\[y = \sum_{j=1}^\infty b_j 3^{-j},\]| where for some \(n\) large we have \(a_j = b_j\) for \(1 \leq j \leq n-1\), \(b_j = 1\) for \(j \geq 1.\) Then $$ | a_j - b_j | \leq 1$$, so |

For large \(n\), the term on the right goes to \(0\), so I can always find a \(y\) close to \(x\) which does not live in \(C\). This argument also establishes that \(C\) is totally disconnected.

Let’s now show that \(C\) has measure zero, one of the most interesting properties so far. So as to not assume too much knowledge of the Lebesgue measure, we have three key properties we want to use (so if you don’t know these, either look them up or just assume them):

(1) For intervals, we have \(\lambda([a,b]) = b-a.\)

(2) If \(\{A_j\}\) a sequence of disjoint measurable sets (meaning within the domain of \(\lambda\)), then

\[\lambda \left( \bigcup_{j=1}^\infty A_j \right) = \sum_{j=1}^\infty \lambda(A_j).\](3) If \(\{A_j\}\) a sequence of measurable sets such that \(A_{j+1} \subseteq A_j\) and \(\lambda(A_1) < \infty\), then

\[\lambda \left( \bigcap_{j=1}^\infty A_j \right) = \lim_{j \rightarrow \infty} \lambda(A_j).\](4) If \(A\) measurable and \(c\) a constant, we have \(\lambda(A + c) = \lambda(A)\) and \(\lambda(cA) = \mid c \mid \lambda(A).\)

Now (3) is clearly useful, since in the construction of \(C\) I made decreasing sets. Let’s calculate \(\lambda(C_n)\) using (1). We have

\[\lambda(C_0) = \lambda([0,1]) = 1.\]Now by our middle thirds construction, we take \(C_0\) and divide it by \(3\), and then add \(2/3\) and divide it by \(3\). Using (4), we get

\[\lambda(C_1) = (1/3) \lambda(C_0) + (1/3) \lambda(C_0) = 2/3.\]In fact, we can just abstractly calculate \(\lambda(C_n)\) using (4) and our construction. Assuming that the weight of each interval is evenly distributed, we get the following:

\[\lambda(C_n) = \sum_{j=1}^{2^{n}} (1/3) \lambda(C_{n-1})/(2^{n-1}) = (2/3) \lambda(C_{n-1}).\]We can then calculate

\[\lambda(C_n) = (2/3)^n,\]and using this plus (3) we get \(\lambda(C) = 0.\)

This summarizes the interesting properties for the Cantor set that we want to study.

The Fat Cantor Set

As mentioned earlier, the fat Cantor set generalizes the above. Instead of removing the middle third from every step, let’s remove maybe the middle fourth. We have to be a little careful on what we mean by removing the middle fourth – unlike the third, there’s not as clean of an interpretation. By the middle fourth, we mean starting at the center of each interval and removing an interval which goes 1/8 in either direction. While the formula for this might be messy, the verbal description is actually sufficient for what we want to do. Since we’re removing a fourth of the interval we have \(\lambda(C_1) = 3/4.\) In the next stage, there are two intervals (of length \(3/8\)), and we want to remove a fourth of those two intervals. So we remove \(2(3/8)(1/4) = 3/16\) from \(\lambda(C_1)\), and we’re left with

\[\lambda(C_2) = \lambda(C_1) - 3/16 = 9/16.\]Let’s abstractly do the case of \(C_n.\) I have \(2^{n-1}\) intervals, and from each one I would like to remove \((1/4)(\lambda(C_{n-1})/(2^{n-1}))\). So in total, we have

\[\lambda(C_n) = \lambda(C_{n-1}) - (1/4) 2^{n-1} \lambda(C_{n-1})/2^{n-1} = \lambda(C_{n-1}) (3/4).\]So by the same logic as above, we have

\[\lambda(C_n) = (3/4)^n \implies \lambda(C) = 0.\]In fact, let’s assume we’re removing a varying amount each time. Take a sequence \((a_n)\) with \(a_n \in (0,1)\) (I can’t remove it all and I can’t remove none of it). Then after removing \(a_n\) at stage \(n\), and using with abstract description, we can calculate

\[\lambda(C_n) = \lambda(C_{n-1})(1-a_n).\]In other words,

\[\lambda(C_n) = \prod_{j=1}^n (1-a_j) \implies \lambda(C) = \prod_{j=1}^\infty (1-a_j).\]Taking the log of both sides, we’re left with

\[\lambda(C) = \exp\left(\sum_{j=1}^\infty \log(1-a_j)\right)\]when this is defined. So, for example, let’s say we want a Cantor set of size \(1/4.\) How are we going to get it based on this? Well, we solve

\[e^z = 1/4 \implies z = -\log(4).\]Without reference to the rest of the problem, let’s try to find a sequence \((b_j)\) such that

\[\sum_{j=1}^\infty b_j = - \log(4).\]A contender might be \(b_j = -\log(4) 2^{-j}.\) To test if this is even possible, let’s try solving

\[-\log(4) 2^{-j} = \log(1-a_j).\]Doing so gives us

\[a_j = -4^{-2^{-j}}+1,\]which is valid given our constraints on \(a_j\)! Let’s now fix any \(\beta \in (0,1)\). Does the above process work for finding a Cantor set with measure of that size? Well, there is some \(z\) so that \(e^z = \beta.\) If we set \(b_j = z 2^{-j},\) then the series certainly works. Now can we solve

\[z 2^{-j} = \log(1-a_j)?\]Taking the exponential of both sides, we getting

\[1 -e^{z 2^{-j}} = a_j,\]and this leaves us with

\[a_j = 1-\beta^{2^{-j}}.\]This certainly works, so we have found a Cantor set of measure between \(0\) and \(1\).

A question to ask now is how much does this generalize the Cantor set? We’ve seen it generalizes the construction, but does it generalize any of the other properties? Certainly the above is uncountable. The fascinating part is that the above is still nowhere dense, meaning I cannot fit an open ball in it but it still has positive measure! This is a very weird thing. For those without measure theory knowledge, one really nice property of the Lebesgue measure is that I can approximate the measure of a set using open sets bigger than it (this is an example of a regular measure). This shows that I can’t go the other way with that approximation – namely, I can’t approximate the measure using open sets from within the set (since, being nowhere dense, this would imply that our set has measure zero).